Australian Food Insecurity

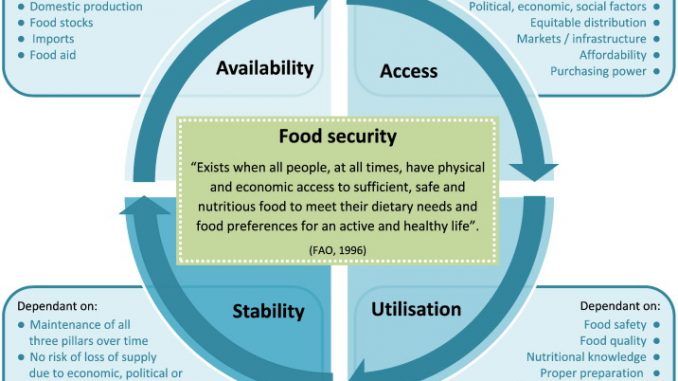

In April 2020, Agriculture Minister David Littleproud claimed that coronavirus was no risk to Australia’s food security. In May of the same year, Littleproud went further in saying that we were one of the most food secure nations in the world, something the Australian Department of Agriculture continues to claim on their food insecurity discussion page, stating that we produce enough of a food surplus that we have the luxury of exporting 70% of it. Food security is considered by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) to be when “all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life”. It would be logical to expect that a nation with a 70% surplus of food would already be feeding all of its citizens beyond their needs.

While the Agriculture Minister is likely correct that the amount of food being produced in Australia exceeds our population’s needs, that production volume doesn’t match the number of people accessing it at the individual level. The Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) pointed out in 2020 that “the most recent estimation of the prevalence of ‘moderate’ and ‘severe’ food insecurity in Australia using the Food Insecurity Experience Scale was 13.4% in 2016-18”. Even these estimates appear conservative given the reporting from food relief organisations in Australia before the pandemic which placed the percentage of food insecure Australians closer to 20% in 2019, or one in five people – a staggering 5.1 million Australians. You can read more about the need for better reporting of food insecurity in our blog.

The Department of Agriculture’s food production figures hide our failure to provide sufficient nutritious food for our people. As more students of food systems understand the true reach of food insecurity in Australia they have begun developing alternative solutions to enable better food access for everyone in this country.

The Global Picture

Sheryl Hendriks from the Institute for Food, Nutrition and Well-being at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, explains that true food security is dependent on each of the FAO’s three dimensions of availability, accessibility, utilisation being met in this order, while a fourth dimension of stability is required for these to be achieved consistently.

Food availability refers to how much food is produced and present in a location. Accessibility refers to people’s ability to reach the food and their capacity to pay for it. Utilisation covers people’s knowledge of how to use the food adequately to maintain a varied and nutritious diet, along with their tools for doing so, such as storage facilities, cooking facilities and cooking utensils.

COVID-19 and recent escalating climate disasters are shocks that have had devastating impacts on global food security through the disruption of availability. These events have revealed the existing weaknesses of current food systems. One of the greatest weaknesses of these systems is the dependence on global supply chains and the massive costs of their disruption. To bolster these chains, a case has been made for better systems modelling to predict and mitigate shocks to these fragile structures. This is certainly logical, given that our dependence on international food systems means that any sudden shocks put us at risk of total system failures. However, it’s possible that these solutions will lead to “more of the same” while ignoring more pressing problems in the concentrated ownership of our food production and distribution.

Franziska Gaupp, Ph.D. frames things succinctly in saying that “the global supply chain of food is concentrated in the hands of fewer and fewer companies” which brings about its own set of challenges. Mary Hendrickson, another prominent researcher in food security has pointed out the increasing concentration of food production companies, which results in smaller producers being increasingly pushed out of agricultural production, the suffocation of local, diversified and culturally relevant food systems, as well as deteriorating soil health and natural diversity through monocropping. While many Australians now reap the benefits of such systems, food security is dependent not only on production and distribution, but on ongoing sustainability. Given what we know about globalised food markets, concentrated production hubs owned by a few big players (oligopolies) are unlikely to be conducive to sustainable environmental health.

But environmental concerns mostly relate to the global availability of food. Philip Howard’s work expands these concerns to how people’s access is impacted by this model, making the case that the concentration of food production tends to “disproportionately affect the disadvantaged—such as women, young children, recent immigrants, members of minority ethnic groups, and those of lower socioeconomic status—and as a result, reinforce existing inequalities.” These worries are consistent with Sheryl Hendriks’ assertion that “most current food insecurity is not associated with catastrophes but with chronic poverty. Recent attention to development failure helps us understand food insecurity as the consequence of structural poverty and inequality.” In short, this means that enabling concentrated power of food production has several disadvantages: the disempowerment of growers and those they serve locally; the disproportionate impact of food insecurity on disadvantaged groups; and the increased food insecurity these parties experience as a result.

Maybe the answer to our problems sits beyond the traditional models we rely on. Very few people and organisations have been willing to address one of the most egregious weaknesses of global food systems where food is assumed to be a commodity rather than an intrinsic right. Arguably, most of the current difficulties in food access could be resolved with a Food Commons model that builds food systems with the right to healthy food prioritised over food’s financial value. By seriously engaging with this idea, we may be capable of building a system that serves all Australians rather than only those with enough money to buy food made through environmentally and socially detrimental methods of production.

The Food Commons Alternative

Common Good Food describes a “commons” as (most often) a natural asset shared between people, where use and maintenance is everyone’s right and responsibility respectively. The most obvious example of this is how we approach land and water, where we these as fundamental needs and generally expect that they be provided as shared public resources. Food commons applies this concept to edible products. The idea posits that food is not a commodity with purely financial value, but rather an essential, commonly available resource to be shared and made available to all people. This may appear radical to those of us in developed nations – after all, it’s hard to imagine a world in which food is simply available to everyone at a low or negligible price. What happens to the Australian economy if 5-6% of our total export product suddenly becomes inaccessible to the market?

It may be a scary idea to economists and investors, but perhaps this restructure is a necessary growing pain for any egalitarian society. Proponents of the idea draw attention to the fact that this system has existed for centuries and continues to exist in many pre-industrial global Indigenous cultures “where taking care of and being taken care of by others and the local environment are indivisible”. Jose Luis Vivero Pol writes in his article for The Broker Online that commodification of an essential resource like food is a development of the last few centuries and we can certainly see that food is such a critical part of a population’s needs that governments have often ensured its constant availability throughout history.

As more people recognise and experience the weaknesses of our current food systems, the Food Commons idea has gained traction as an increasingly appealing framework for future food systems and it’s not hard to see why. The idea provides some answers to individual and household level food insecurity through promoting non-hierarchical sharing of knowledge, processes and property in order to grow and distribute food for the local community. And while this sounds like the answer to all our problems, it’s clear that no system is without weakness. What is being proposed is simply an attempt at designing a more inclusive and just food system, not a universal panacea that will either fix humanity’s intrinsic flaws or overcome the limits of market forces. As such, this framework does not preclude food as a market commodity altogether, but prioritises its role as a common good and gives us a jumping point to consider more humanitarian policies beyond the status quo of hunger and poverty.

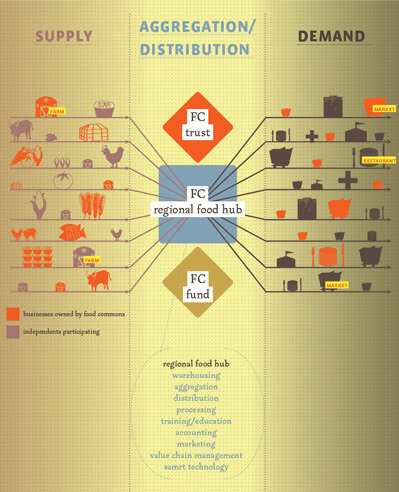

Current food commons ideas are often based around Vincent and Elinor Ostrom’s work on various centres of governance (polycentric governance) related to food. The idea is that food governance operates at local, state and national levels with each part exercising some degree of autonomy while taking the others into account. Again, Jose Luis Vivero Pol guides us through this model’s three governance pieces, with the first component of civic collection actions for food (AKA Alternative Food Networks) undertaken at the local level as a means of responding to immediate local needs. This definition is ambiguous but can most easily be thought of as short supply chain systems. Some examples already exist in Australia such as purchasing directly from producers as with the Open Food Network, purchasing fruit and veg at greatly discounted prices as with The Community Grocer and food waste diversion from landfill to the community such as Foodbank, Secondbite and Ozharvest.

The second piece, Luis says, is government responsibility for providing an “enabling framework for [citizens] to enjoy the food commons (food as a public good).” In Victoria (state level), this may include supportive policy, initiatives, and establishment of organisations such as VicHealth which operate semi-autonomously to improve Victorian social outcomes. Naturally, this can also occur nationally with programs like the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Program, but may not be focused on food commons so much as attempting to address food insecurity using traditional economic models.

Finally, the private sector may continue to trade in “undersupplied, specialised or gourmet foodstuffs (food as a private good).” Luis tells us that in this system, the private food sector behaves as private schools and hospitals do besides public systems.

Unfortunately, many of these ideas remain theoretical and finding reliable guidance around food commons implementation can be frustrating since so few papers or articles explore the idea and provide clear examples of how it might work. It’s that nebulous nature which it strength as a generalisable concept as well as a weakness in that the broader public is unsure of how to implement something that remains largely academic.

Thankfully, we have local examples as described above to begin to understand how a commons may behave in replacing our current system and there continue to be global examples of commons-based approaches following the COVID crisis and its aggravation of existing inequities in our food system. Dr. Jennifer Clapp has written various papers on better food security policy. She has also spoken on the Feed podcast about practical solutions such as: redirecting subsidies away from trade and agricultural production to locally based agroecological solutions; amending global trade rules to protect the livelihoods of marginalised farmers in low income countries; and improving the ability for small enterprises to compete in the market. A working food commons model seeking funding has also been created by organisations like The Food Commons in the USA which aims to build a dedicated body that enables the formalised promotion and oversight of a national commons.

What Now

As larger proportions of the population experience and witness the devastating effects of food insecurity, we have seen increased adoption of, and mobilisation around the idea of food as a commons. Women News Network points out that “self-governing collective actions cannot create the transition by themselves” and that we need to give the state “a leading role in the initial stage of the transition period to guarantee food for all.” Certainly, it should be the role of government to enable and facilitate access to food for all but, for now, collective civic action remains the most effective method by which this can be, and has been, achieved. If Food as Commons is a viable way forward, then it should be enabled by governing structures which will need support and action from the people – at least, in the beginning.

We have already seen the critical weaknesses of our existing food systems and its failures in feeding a growing number of Australians. Beyond this, we have had to reckon with this system’s fragility as climate change and COVID shocks bring our production and supply chains to a halt. As we move forward in making food systems decisions, we need to consider the essential function of food and the capacity of greater ‘commonification’ to provide this essential resource to all. In developing stronger food security, we should be attempting to build food systems in a way that Australians can achieve sufficient, culturally-appropriate nutrition regardless of their income while supporting improved environmental and social outcomes. For this reason, the Food Commons idea holds a lot of potential and should be part of ongoing legislative conversations.

Food Commons may be able to rebuild national food sovereignty and create secure, sustainable, nutritious, safe and culturally appropriate food for a greater number of Australians. As such, the concept provides a real avenue to establish a food system we can collectively be proud of. In the precise words of Mary Hendrickson: our only hope is that the precarity of the system, its potential losing of its core identity as a for-profit food system based on efficiency, specialization, standardization and centralization, will allow transition to a decentralized, diverse, and interconnected food system that can feed all of us now and in the future.

About the author

Camilo Cayazaya is a dietitian, educator and writer with a love of public health, food sovereignty and social equity. He holds a Master of Dietetics and Bachelor of Communications in Print Journalism and Screen Studies and currently works as a contact tracer for Monash Health’s South East Public Health Unit. He is always looking for opportunities to help build greater collective knowledge and participate in improving existing systems.